Herbal Illuminati

December 11th, 2025

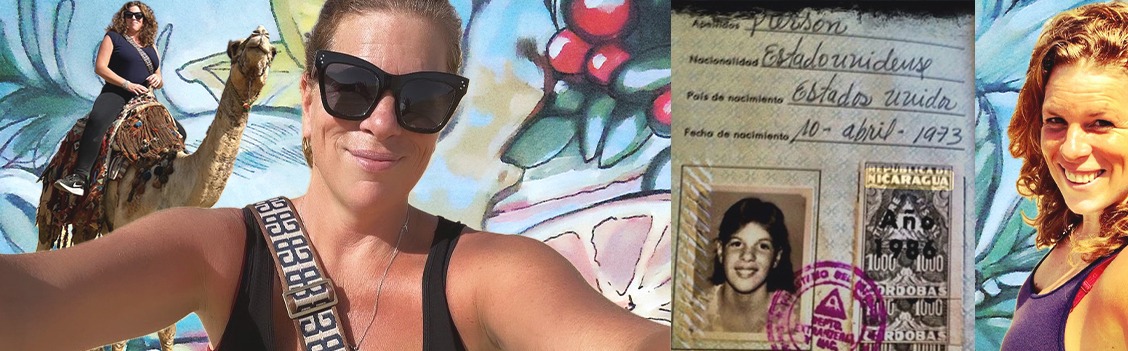

The current Herbal-Roots (2025) winter collection, Illuminated Juxtapositions & Enlightening Travel, didn’t begin this year or in this season. Like all my herbal artistry, it was born from transformation, and this collection began taking shape long ago, when my global travel started at age 11. Wanderings that carried me through Nicaragua, Israel, Italy, Greece, Ecuador, Mexico, China, Vietnam, Berlin — places that imprinted themselves on how I cook, taste, move, observe, and understand herbs, and on how I understand those who love herbs the way I do. These herbal mixtures come from the same lived learning that built My Herbal Roots: a life shaped by wandering, carrying myself through different cultures and kitchens, watching how flavor behaves in the world, how people behave around food and otherwise, and by letting those impressions settle deeper into my natural instinct.

My herbal artistry has always been tied to my wanderings. Travel sharpened what herbs already asked of me — attention, simplicity, curiosity, humility. Being young inside unfamiliar rhythms, learning the taste of the unknown, being stretched by contrast and softened by generosity — all of it carved my foundation.

The following illuminati offers a more intimate look at place, for each of my winter 2025 offerings— a set of short place-stories that trace the noticing behind each mixture, offering context, nostalgia, and the small relearning’s that make this collection feel especially alive.

If you’re here reading this, and notice its incomplete, know I’m working on getting all the short stories posted soon. I’ve overextended myself in the most serious holiday way.

Swimming in the Crater of Volcano

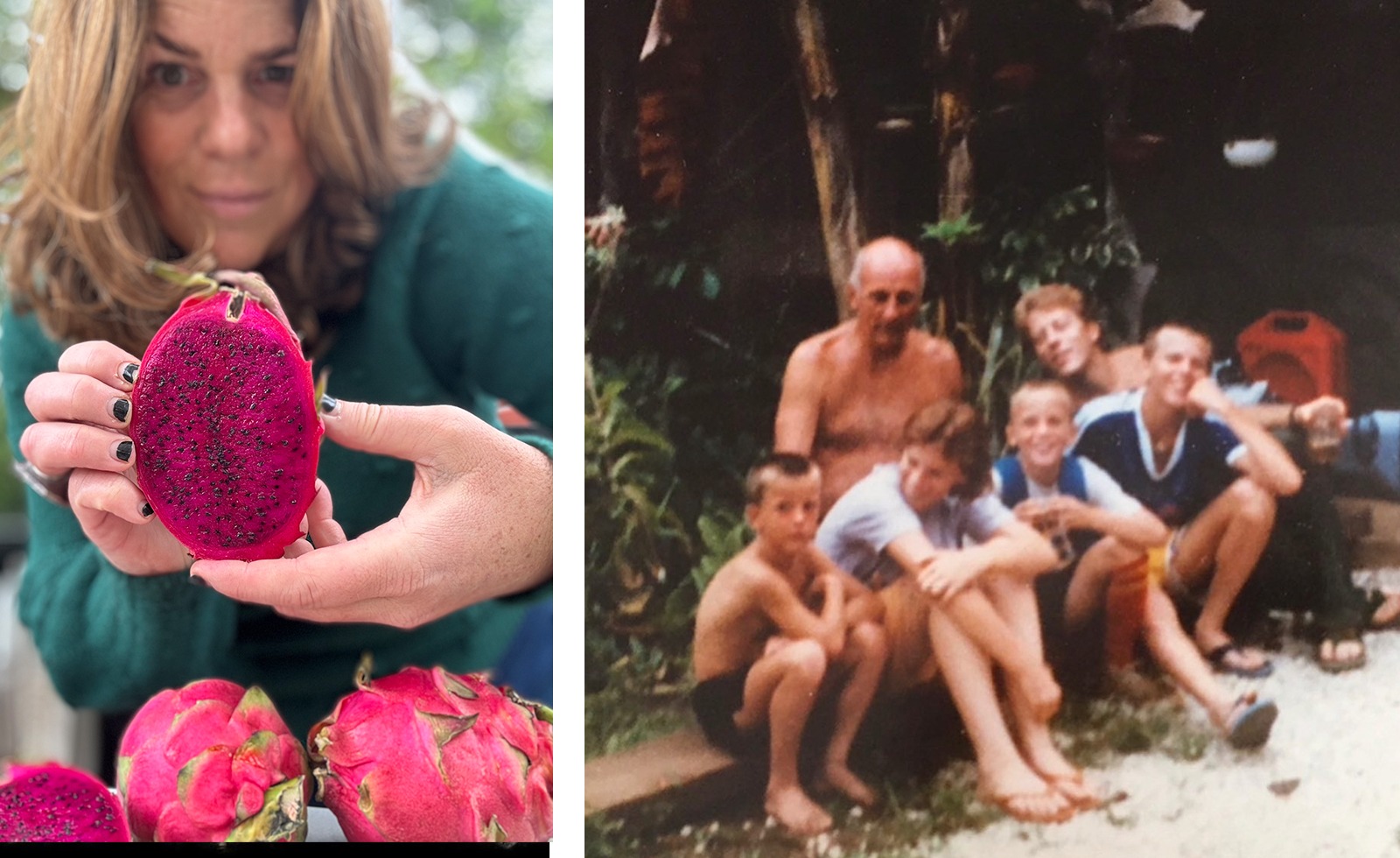

Pitaya Nicaragüense Herbal Citrus Salt

In 1985 when I was 12 years old, my father—who had summer custody of me and my three brothers after a few years of bitter custody battles, which is when I first realized how little adults take kids seriously and how unreliable most of them are—loaded us into a red GMC pickup with a camper shell, pulling a small camping trailer outfitted with a tiny kitchen and a few fold-out beds. He packed power tools, seeds, and other things he thought would be necessary. None of that was known to us at the time. All we knew was that we were going on an adventure.

And that we did. That is where my travel illuminati first got sparked.

We drove from Palmdale, California to Nicaragua via the Pan-American Highway—down the coast of Mexico, over railroad bridges suspended high above jungles because roads had been blown up in El Salvador, through thick jungle stretches of steep Guatemala mountains and agricultural parts of Honduras.

After a month of driving and learning quickly how different things were just south of where we grew up in southern California, we landed in Managua, where all five of us lived in that camper trailer. Soon after, through the kindness of “I Like a Strong Cheese, Joseph” (a story for another time), we ended up in Masaya, a small city in western Nicaragua, located south of Managua and near the Masaya Volcano and Laguna de Apoyo. It’s a city well known, then an now, for its vibrant culture and commercial hub known for indigenous handicrafts like hammocks and pottery. The city then and now has one of the largest and busiest active central markets in the country.

In 1985, Masaya was marked by the Sandinista period and the ongoing Contra war. The city was active but strained—fuel, food, and goods were limited, and daily life was shaped by shortages, rationing, and political presence. Markets still functioned, crafts were still made, and people carried on with work and family life, but there was a constant backdrop of uncertainty, military activity, and economic pressure.

What struck me then as a little American girl in a strange place, completely out of my element but so open, and still does now, was the vibrancy of Masaya. We lived in a small tin-roofed house with open eaves, tile floors, and a very plain, basic structure. There was a covered outdoor cement kitchen and washbasin, a covered porch, and about a hectare of land planted with fruit trees—fruits I had never imagined existed, with flavors I had never known.

At the edge of the property was a dirt-floor, tin-roofed caretaker’s house where an entire family lived in two rooms and cooked over firewood.

Pitaya grew everywhere on the property. Long, flat cactus stems with soft linear ridges draped and sprawled, anchoring and spreading like spider legs. In the wild they clung to trees and vines, but here, on our small Masaya finca—as these little houses with land and fruit were called—they were cultivated in rows, strung up with twine supporting the limbs. The large white flowers bloomed at night and released a sweet, heavy floral scent that carried through the warm air. That scent lingered in Masaya. I remember it clearly. It was in Masaya, that I first became infatuated with pitaya, and with noticing vibrancy everywhere.

In Masaya, I had my first sip of the pink juice—a simple agua fresca made from pitaya, sugar, and lime. It was the brightest magenta-fuchsia color I had ever seen, with a delicate melon-and-lime flavor unlike anything I had tasted. As a little American girl, it was my first sense of what I didn’t yet know I had been missing: a taste, a color, a scent that felt unimaginable to me—fresh, alive, and vibrant—drawn from a strange cactus, made entirely by hand from fruit picked straight off the plant and sugar scooped from plastic bags in a busy open-air market.

Open-air markets that not only served this nectar of pitaya and lime, but a bevy of tastes and scents and an energy that still has potency inside me.

Despite the economic and political pressure on the adults, what I remember are the restaurants, which were nothing more than about thirty make shift square outdoor kitchens with high seats, gigantic, charred cast-iron pots lined up around these makeshift outdoor kitchens fueled by burning wood, the air thick with smoke. People sat around plywood countertops. Large plastic vats held shredded green cabbage, salted and lime doused.

Gallo pinto, the staple of Nicaraguan cuisine, was comingling in dirty pots everywhere. The smell of that market is something I will never forget. The taste of bistec—sliced beef stewed with tomatoes, onions, and whatever else—spooned over those gallo pinto (rice and beans fried together with cilantro), lime cabbage tucked on the side, a few sweet fried plantains, and a glass of pitaya-lime juice, is one of my strongest Masaya memories. It was a meal repeated again and again while we lived there, and it never got old. Despite poverty—ours and theirs at the time—we all had enough, and what we had was incredibly vibrant.

After market days, my dad would drive us to Masaya Volcano and Laguna de Apoyo, a volcanic crater lake formed by a collapsed volcano. The water was the bluest electric cyan—teal—warm like lava, and one of the most incredible bodies of water I have ever submerged myself in. The lake sits far lower than the surrounding land and doesn’t offer many shallow edges, but we were California beach kids and strong swimmers. I remember diving straight down and never touching the bottom. We were like lava fish there, swimming in a pool of aquamarine water in a hole surrounded by baren and high volcanic black soils.

If I remember correctly, we would also slide down the volcanic soil slopes—on something I can’t quite recall—straight into the water. We were adventurous kids, and Nicaragua only amplified that. There were many contrasting realities happening at once, but through my child’s eyes it all felt wondrous, joyful, and simple. Pleasurable.

We went on to Managua, Nicaragua, after some months in Masaya, and lived on an old coffee plantation. It had gigantic, tiered, dirty concrete coffee pools, used for washing, surrounded by numerous concrete benches overlooking all of Lake Managua and Lake Nicaragua. Thick green jungle framed most of the property, which was filled with mango trees, monkeys, macaws, and wild energy. It was extraordinary, dilapidated, battered, maybe even unsound, and breathtaking all at once—It remains one of the most beautiful properties I have ever seen. I still feel lucky to have lived there.

No one reading this would feel comfortable living there with their kids, that’s for sure, but we did, I did and I am still enamored with it. But this too is a story for another time—as is the poverty, Ringo and Lingo, my Nicaraguan dogs, smuggling DDT into Costa Rica for the pineapple trade, and Daniel Ortega, who was president then, just as he is now